EE3901/EE5901 Sensor Technologies Chapter 4 NotesCapacitive sensors and signal conditioning circuits for reactive sensors

Changes in capacitance provide another mechanism for electrical sensing. In this chapter we will discuss some common capacitive sensors, as well as the interface circuits that are used to measure changes in capacitance.

Capacitance

Firstly, let’s review the physics of capacitors. A capacitor consists of two electrodes separated by an insulating material. An accumulation of charge on the electrodes creates an electric field between the plates. The electric field causes the effects we know as capacitance.

Capacitance is measured in farads (F), which is equivalent to coulombs/volt. In other words the capacitance tells you how much electric charge will accumulate on each electrode per volt.

Suppose we have rectangular electrodes, as shown in Figure 1.

The basic geometry of plane-parallel capacitors. There are two conductive electrodes (yellow) separated by an insulating material (transparent grey). The electrodes have surface area

These are called “plane parallel” electrodes. These serve as a prototypical example of a capacitor, and serve to explain most of the important physics.

The capacitance of plane parallel electrodes is given by

where

where

Fringing effects

The geometric capacitance (

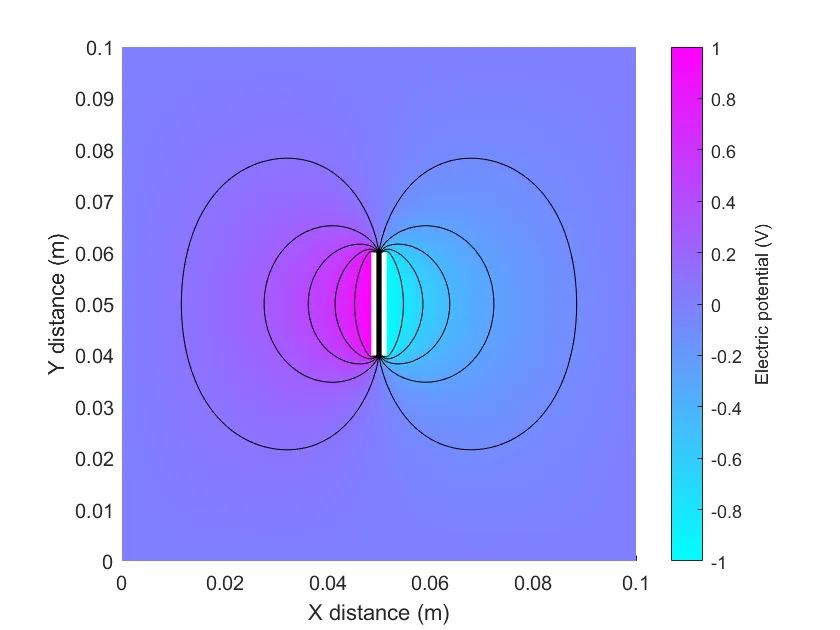

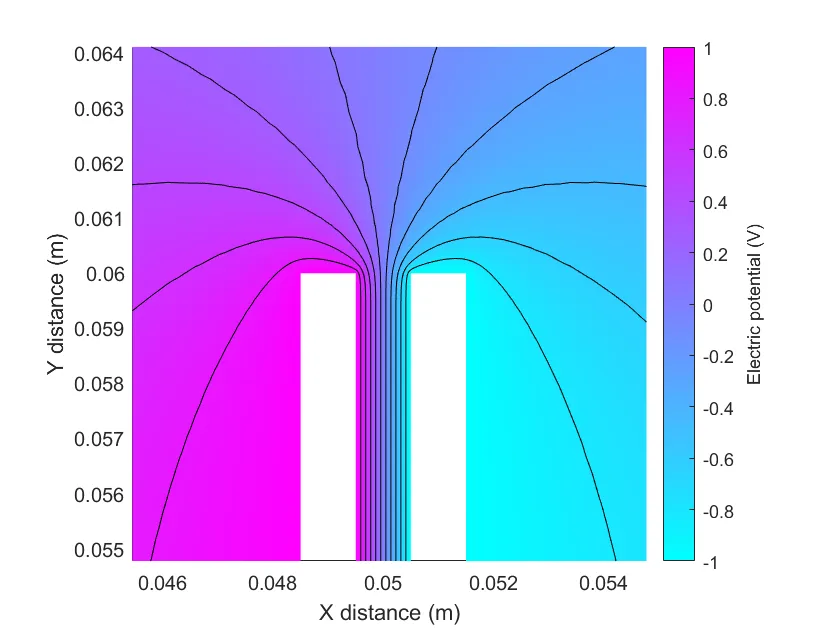

The calculated electric potential in the vicinity of plane parallel electrodes. This is a slice through the middle of a capacitor. The electrodes are the white rectangles, and you should visualise them as being extruded into the page. The left and right electrodes are connected to

A zoomed in version of Figure 2, showing the region of fringe effects at the edge of the electrodes.

Zoom:

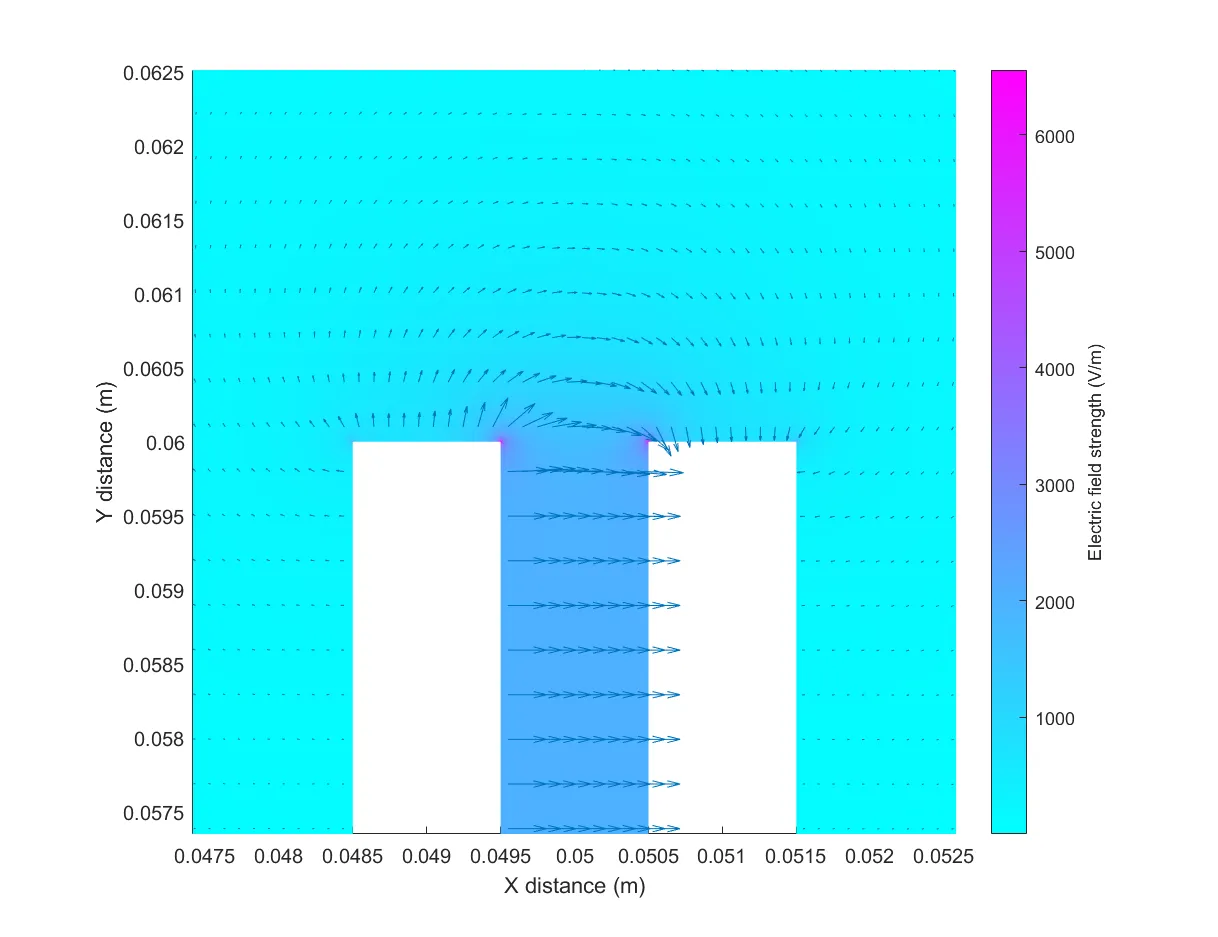

The electric field for the same capacitor as Figures 2-3. Notice the uniform electric field between the plates, the strong electric fields at the corners of the electrodes, and the fringing fields that weakly extend outside the capacitor’s main body.

Zoom:As shown in Figure 4, the electric field lines curve outwards near the edge of the capacitor. If this system were a sensor, and our goal was to measure changes in capacitance, these fringing effects may cause interference. For sensing purposes, we can minimise the edge effects by using guard plates (Figure 5).

A capacitor with split electrodes. The sensing electrode is the central plate shown in red. The adjacent electrodes are energised in the same manner, so that the neat parallel electric field lines are preserved in the vicinity of the sensing electrode.

Zoom:Using these guard electrodes, the capacitance between the middle electrodes is closer to the ideal geometric value,

Mechanisms of capacitance sensing

Using the equation

- Changes in area (e.g. by moving the electrodes sideways so that the area of overlap varies); or

- Changes in separation distance (e.g. by moving the electrodes closer together or further apart); or

- Changes in permittivity (e.g. by changing the properties of the material between the plates).

When we consider also the equivalent circuit of multiple capacitors, we can identify another mechanism:

- Introducing or removing nearby objects that are capacitively coupled to the sensor, thereby adding or removing a capacitors from the equivalent circuit of the sensor.

Some mechanisms are shown in Figure 6.

Examples of how capacitance can be used as a sensing mechanism. (a) Movement of electrodes causes variation in overlap area. (b) Capacitance is highly sensitive to the separation distance, so a common mechanism is to vary the distance between electrodes by moving or stretching the materials. (c) A dielectric material can be moved or undergo changes to its permittivity, for example, in a humidity sensor by absorbing water. (d) Capacitive touch screens operate by detecting the formation of new capacitive coupling.

Zoom:Capacitive humidity sensors

Capacitance is a useful mechanism to detect water because water has a high permittivity. (This is because water molecules are polar, and can easily orient themselves in response to an applied electric field.) The relative permittivity of air is

A typical mechanism is to use some absorbent material that takes up moisture from the air. A properly chosen absorbent polymer film can be used to create an almost linear relationship between capacitance and relative humidity. However, the permittivity varies with temperature, so the temperature must also be measured and corrections applied.

Capacitive level sensors

Capacitance can be used to measure the level of liquid, as shown in Figure 7.

The concept of water level sensing. (a) Capacitive electrodes are inserted in or near the liquid. (b) Electrically, this behaves like the parallel connection of many capacitors.

Zoom:The electrodes may have various geometries, for example, they may be cylindrical with an inner electrode and an outer electrode where the liquid travels up the middle like a pipe. Alternatively they may have flat electrodes arranged as parallel plates or coplanar plates. If the electrodes are inside the liquid, then they must be covered with an insulating material. Alternatively, the electrodes may be placed on the outside of the container walls.

Since the air and liquid have different permittivity values, the capacitance per unit length in the air and liquid region are different. As the water level rises, the proportion of the capacitor with a high permittivity increases, resulting in a close to linear increase in capacitance.

Again there is a temperature dependence that must be accounted for. One strategy to do this is to include two more electrode pairs to measure the capacitance of the liquid and air. This can be used to correct for changes in temperature.

Other applications

- Capacitance can be used to measure small displacements by moving the electrodes with respect to each other. For example some accelerometers measure the deflection of a proof mass suspended on a miniature spring.

- Studio condenser microphones measure the deflection of a diaphragm through change in capacitance.

- An electrically conducting object can be used as one electrode in a single ended capacitance probe.

Capacitive interface circuits

Interface circuits for capacitive sensors often use a sinusoidal voltage

or current. In this case, the capacitive sensor can be represented

by a complex impedance

For some intuition, consider a capacitance sensor with

However, there are also various circuit designs that are more specialised to capacitive sensor interfacing.

The auto-balancing bridge

The auto-balancing bridge (Figure 8) is a simple circuit that is common in LCR meters. To understand this circuit, notice that the op-amp creates a virtual ground at

The auto-balancing bridge circuit for capacitance measurement. This design is suitable for measurement frequencies below about 100 kHz. At higher frequencies, op-amps do not have enough gain-bandwidth and so different circuit designs are needed. (For more details, a good reference is the Keysight Technologies Impedance Measurement Handbook.)

Zoom:Op-amp circuits with linear responses

When impedance is linearly proportional to the measurand

Consider a capacitive sensor where the separation distance is varied. Specifically, consider that the distance is given by

where

where

Now consider the impedance of this capacitive sensor:

Notice that impedance is linearly proportional to the measurand. A suitable interface circuit is shown in Figure 9.

An op-amp based circuit where the output voltage is linearly proportional to the sensor’s impedance.

Zoom:The resistor

where

Notice that the output is linear with respect to

When impedance is inversely proportional to the measurand

Other types of capacitive sensors may have variations in permittivity or surface area, i.e. a response of the form:

In this case the capacitor’s impedance is

i.e. impedance is inversely proportional to the measurand. In this case, swap the placement of the variable and fixed capacitors:

An op-amp based circuit where the output voltage is inversely proportional to the sensor’s impedance. Equivalently, the output voltage is directly proportional to the sensor’s admittance.

Zoom:The resulting output voltage is

Again notice that the output voltage is linearly proportional to

AC bridges

Bridge circuits can also be used for capacitive sensors, as shown in Figure 11.

A generalisation of the Wheatstone bridge, used to measure the AC impedance of a sensor.

Zoom:The analysis is similar to the Wheatstone bridge except that impedances are used instead of resistances.

A variation of this concept is the Blumlein bridge, where a centre-tapped transformer is used on one side (Figure 12).

The Blumlein bridge circuit is a variant of the Wheatstone bridge where one side is a centre-tapped transformer. At least one of the impedances

The advantage of this design is that the sensing side has galvanic

isolation from the excitation source, so that it can be separately

grounded. Notice that

To analyse this circuit, notice that the action of the transformer

is to produce a voltage source with magnitude

Circuits based on charging & discharging capacitors

Transformers cannot be miniaturised, hence other interfacing circuits have been developed for integrated circuits. Instead of using sinusoidal excitation, capacitance can also be measured based on its charging and discharging behaviour.

Charge transfer

Charge can be transferred from an unknown capacitor to a known capacitor (Figure 13).

Simplified circuit diagram showing the principle of capacitance measurement by transferring charge between capacitors.

Zoom:This circuit operates in three steps:

- The unknown capacitor

- The energy stored in

The output voltage can be derived by conservation of charge. You will show in tutorial questions that

Variable frequency oscillators

An oscillator is a circuit that produces a periodic waveform. A common strategy to measure capacitance is to design an oscillator circuit whose output frequency depends upon the capacitance of the sensor. An example is the relaxation oscillator that uses a comparator (Figure 14):

The relaxation oscillator circuit, which is an capacitance measurement circuit suitable for frequencies up to tens of kHz.

Zoom:The sensor can be either

As drawn, this circuit is for a comparator with push-pull outputs,

for example the TLV3491.

The pullup resistor

Other types of oscillators (e.g. Wein bridge oscillators, Hartley oscillators, and Colpitts oscillators) operate at higher frequencies, and hence can be used with sensors whose capacitance is smaller. The principle is the same: changes in capacitance cause changes in oscillation frequency, and the frequency is then measured with a microcontroller or other digital circuit.

Designing capacitive sensors

If a capacitor has plane-parallel geometry, then the capacitance is given by the well-known formula

However, what if the system does not have this geometry? There are a few special geometries where exact solutions are known, but in general, there is no formula sheet for the capacitance of any arbitrary shape. If there is no simple formula, then we must turn to computer software to calculate capacitance. This week, we will learn how to calculate capacitance for any geometry that you can draw in a CAD package. We will do this using the finite element solver in Matlab’s PDE toolbox.

The meaning of capacitance

The meaning of capacitance can be understood through the formula

where

Equation (1) will be our recipe for calculating capacitance. We will set up a computer simulation with a given voltage

Recap of electrostatics

Electricity and magnetism are described by Maxwell’s equations. However, for the purposes of analysing capacitors, we will simplify Maxwell’s equations by applying the electrostatics approximation. We will also assume that there is no free charge outside of any conductor.

With these approximations, the key physics is Gauss’s law,

where

However, for numeric calculations, it is convenient to calculate the electric potential (aka voltage) at every point, instead of the electric displacement. This is because the potential is a scalar value. The relevant equations are

where

Capacitors are created when there are two or more conductors. We will assume that the conductors are ideal. This means that the potential is the same everywhere within the conductor. (In the language of circuit theory, the entire conductor is a single node.)

Therefore, the important and interesting physics is what happens in the region outside the conductors. Our problem formulation will look like Figure 15. This is a 2D slice through a general 3D geometry. In this example figure, there are two rectangular conductors shown in white. These should be viewed as extending into the page to create the overall 3D structure.

The calculation domain for an electrostatics capacitor problem. The region in grey is the domain in which we need to calculate the electric potential. Black borders indicate the edges of this domain. At every edge, we will specify a boundary condition in the form of a voltage.

Zoom:We will solve for the potential in the region between and around the conductors. To set up the problem, we must specify:

- The voltage at every edge, and

- The permittivity at every point within the domain.

From this, we can numerically solve Eq. (5) to obtain the electric potential.

There is one final piece of electrostatics theory that we will need. Gauss’s law can be converted into the so-called “integral form”, which reads:

where the integration is around a closed contour

The case of more than two conductors

Some capacitive sensor designs will need electrodes to act as shields. Therefore, we need to define a capacitance matrix, as a way to describe the capacitive effects between systems of conductors.

Firstly, let’s consider just one conductor. Even a single, isolated conductor has capacitance. Suppose that you place some electric charge on this isolated conductor; then the charge will induce an electric field in its vicinity. These electric field lines must terminate somewhere. By convention, we define self-capacitance as the capacitance between the object and a conducting sphere at infinite distance.

Capacitive interactions between 3 conductors. Each conductor has a self-capacitance

Now, suppose that there are multiple conductors in the system. As shown in Figure 16, there will be interactions between all pairwise combinations of conductors. These are called mutual capacitances. We can express the mutual capacitances in a matrix as follows:

where

The Maxwell capacitance matrix

Let’s analyse the 3-conductor system of Figure 2 more closely. The charge on conductor 1, given a certain arrangement of voltages, can be obtained by summing up the contributions due to each capacitor shown in the figure:

However, Equation (8) is not very convenient to use because the expressions involve differences between voltages. It would be nicer to treat all voltage terms as being defined with respect to a common ground reference, just like we normally do in circuit theory. We would prefer an equation of the form:

If we expand the brackets in Eq. (8) and equate coefficients to those in Eq. (9), we find

In general we have

This leads us to define the Maxwell capacitance matrix as follows:

Notice that the off-diagonal terms in the Maxwell capacitance matrix are negative. The physical meaning of the negative sign is that a positive voltage on one conductor induces a negative charge on another capacitor.

Given some entries in the Maxwell capacitance matrix, we can find the mutual capacitances by inverting Eqs. (5) and (6) to obtain

Overall, we can see that there are two ways to define a “capacitance matrix” for a multi-conductor system. The matrix of mutual capacitances has the advantage that the network can be analysed via circuit theory to find the parallel combination of capacitors between any two conductors. Conversely, the Maxwell capacitance matrix has the advantage that it is easy to calculate. We will describe the process to calculate the Maxwell capacitance matrix next.

How to calculate capacitance

Consider once more the 3 capacitor system of Figure 2. Suppose that we apply a voltage to conductor 1, and we ground all the other conductors. Therefore, substituting

which leads to simple expressions for the first column of the Maxwell capacitance matrix:

Next, we apply a voltage to conductor 2 and ground all the other conductors, to calculate the second column of the Maxwell capacitance matrix. Continuing in this way, we obtain the full description of all capacitive interactions in the system.

Practical example

Below is an example of analysing a real example using Matlab’s PDE Toolbox.

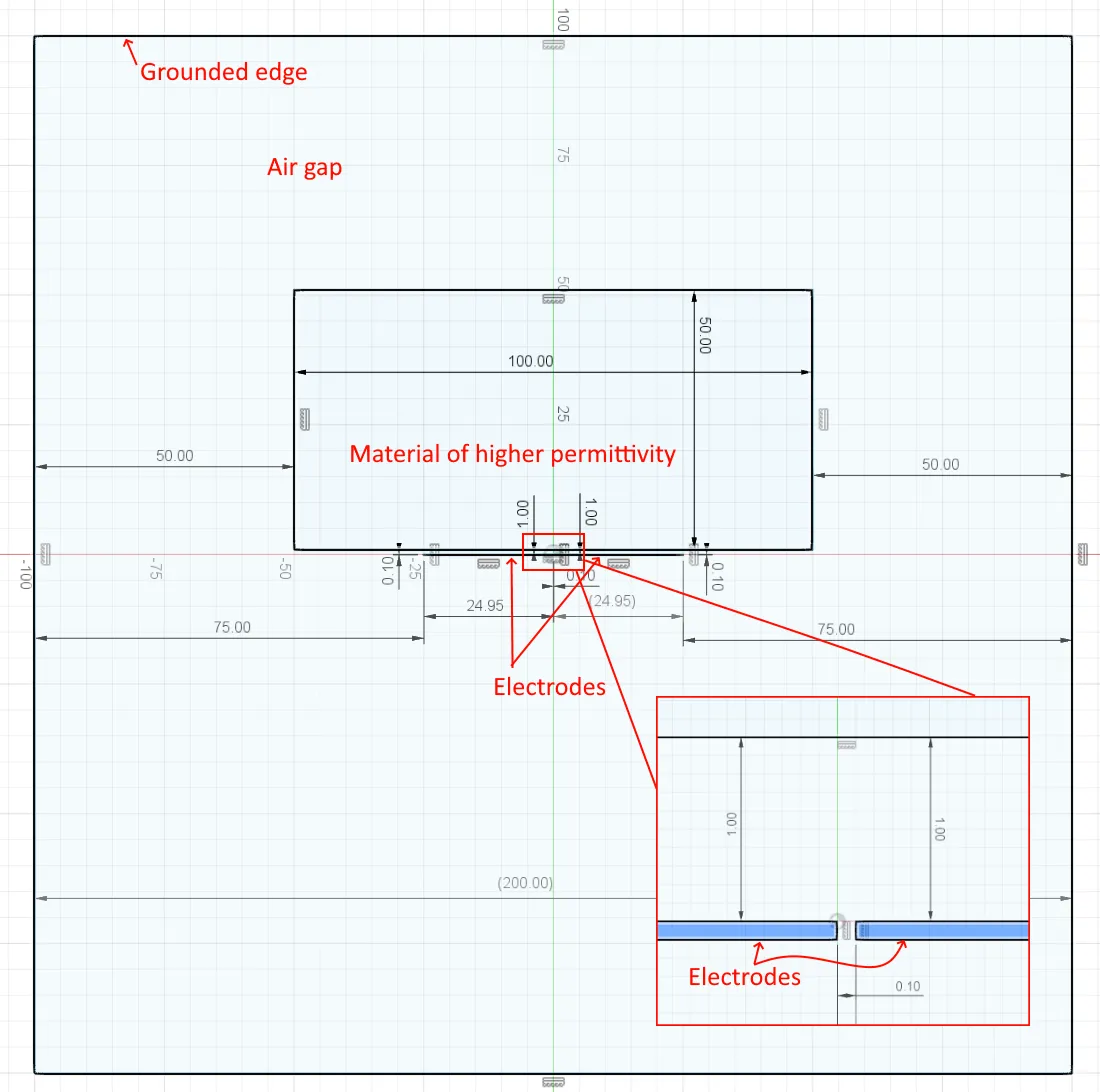

Defining the geometry

Firstly, you must draw the geometry that you wish to calculate. The geometry must cover the region surrounding the conductors with a sufficiently large “air gap” around the outside. Typically the easiest way to do this is to define a large rectangle, then draw features within this region. The features you draw will be either conductors or regions of differing permittivity. An example is shown in Figure 17.

Example of drawing a capacitive sensor in the Fusion 360 CAD software. Dimensions are specified in mm. There are two thin electrodes (0.1mm x 24.95mm) separated from each other by 0.1mm. There is a region of higher permittivity located near the electrodes. The inset shows a zoomed in section at the centre of the drawing.

Zoom:The Matlab PDE toolbox requires geometries specified in the STL file format. For 2D problems, such as this, the STL file must have all its geometry lying with a plane. This means that you cannot extrude your sketch into a 3D shape, because the result will be a 3D geometry that will be treated by Matlab as a 3D problem.

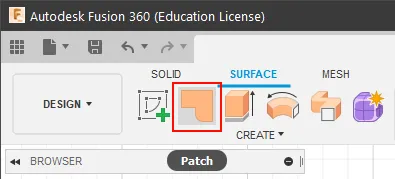

To generate a planar geometry in Fusion 360, select the “Surface” toolbar and click “Patch” (as shown in Figure 18).

The location of the Patch tool.

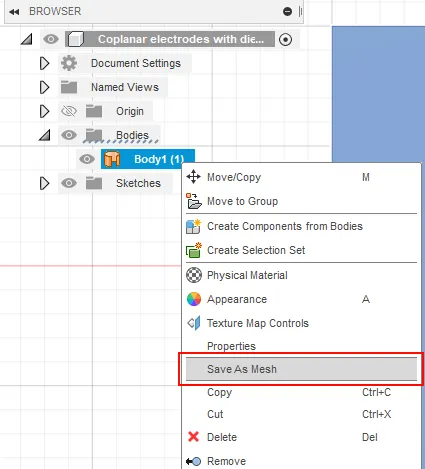

Zoom:Next, click on the air gap part of the sketch to create the patch. There will be holes in the patch where the electrodes and other features are defined. You can then export this patch to an STL file by right clicking on it in the browser and selecting the Save As Mesh option (Figure 19).

Generate the STL file by using the Save As Mesh feature.

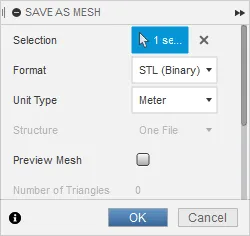

Zoom:You should export the STL in binary format using metres as the dimension (Figure 20), since if you specify geometry in SI units then you avoid having to perform unit conversions later.

Selecting meters as the dimension means no further scaling is necessary once you load the geometry into Matlab.

Zoom:You may download this example geometry as:

Loading the geometry into Matlab

The STL file is loaded and displayed as follows.

%% Load geometry and show the edges

geometry = importGeometry('geometry.stl');

figure();

pdegplot(geometry,'EdgeLabels','on');

xlabel('X distance (m)');

ylabel('Y distance (m)');

The geometry with the edges labelled. In this case, you would need to use the zoom controls in the Matlab figure window to identify the labels that appear to overlap.

Zoom:By zooming in on the figure in Matlab, you can identify which edges correspond to which features.

% specify the edge IDs

outside_edges = [2 4 11 13];

dielectric_edges = [7 10 15 14];

electrode1_edges = [4 1 8 6];

electrode2_edges = [9 12 5 16];This geometry currently has three “holes” in it. There is a hole where we intend to place the dielectric, and a hole for each of the electrodes. The dielectric must be “filled in” so that the electric potential will be calculated in this region. This can be done using the addFace function:

% fill in the dielectric region

geometry = addFace(geometry, dielectric_edges);

% leave the conductors as holes in the geometry

% show the faces

pdegplot(geometry,'FaceLabels','on');Notice that the electrodes are left as holes. This is important. The Matlab PDE toolbox can only specify voltage boundary conditions at the edges of the domain. Therefore, every conductor must be treated as a gap within the domain. If you accidentally use addFace to fill in a conductor, then the voltage specified there will be completely ignored.

Preparing the mesh

The finite element solver uses triangular meshes to represent the geometry. You need smaller meshes near the electrodes (to capture the rapid variation in voltage in this region). This can be achieved using the HEdge parameter when calling generateMesh.

%% create the model and look at the mesh

emagmodel = createpde('electromagnetic','electrostatic');

emagmodel.Geometry = geometry;

generateMesh(emagmodel, "HEdge", {[electrode1_edges electrode2_edges], 1e-5});

figure();

pdeplot(emagmodel);The mesh geometry generated using the code above.

Zoom:You must have the mesh covering all the dielectric regions, and there must be a hole in the mesh for each conductor.

Setting material properties and boundary conditions

%% Set material properties

emagmodel.VacuumPermittivity = 8.8541878128E-12;

electromagneticProperties(emagmodel, "Face", 1, "RelativePermittivity", 1);

electromagneticProperties(emagmodel, "Face", 2, "RelativePermittivity", 15);

%% Set conductor 1 to 1V and others to 0, and find the charge on each conductor

electromagneticBC(emagmodel, "Voltage", 1, "Edge", electrode1_edges);

electromagneticBC(emagmodel, "Voltage", 0, "Edge", electrode2_edges);

electromagneticBC(emagmodel, "Voltage", 0, "Edge", outside_edges);

% Solve

R = solve(emagmodel);

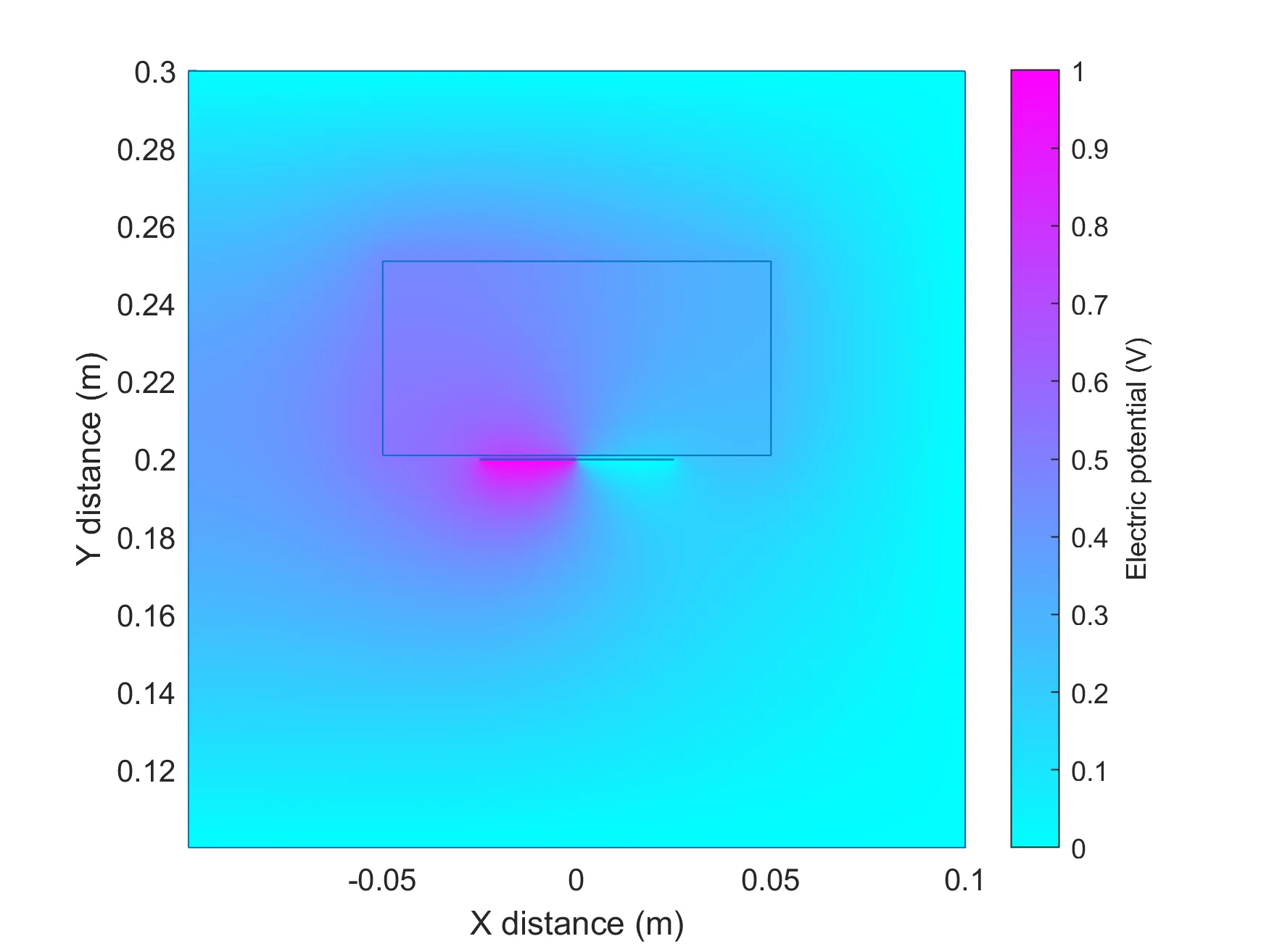

% Plot electric potential

figure()

pdeplot(emagmodel,'XYData',R.ElectricPotential);

xlabel('X distance (m)');

ylabel('Y distance (m)');

c=colorbar(gca());

c.Label.String = 'Electric potential (V)';

axis tight;

axis equal;

hold on;

pdegplot(geometry);

The electric potential computed using the above code. Notice how the region of higher potential extends further into the high dielectric material than it does into the air gap below the electrodes.

Zoom:Calculating capacitance

Recall that to calculate capacitance we need to know the charge on each conductor, and for that, we must perform a line integral around the conductor:

The attached code implements a function charge_on_conductor() that will perform this integral.

Given the solution above (where conductor 1 has a voltage of 1V, and all other conductors are grounded), the entries in the Maxwell capacitance are given by the code below.

C11 = charge_on_conductor(R, electrode1_edges)

C21 = charge_on_conductor(R, electrode2_edges)

% Calculate the mutual capacitance

Cm12 = -C12

Cm11 = C11 - Cm12The results (for the values in the code above) are

Since this is a 2D problem, it represents a slice through a real 3D geometry. Therefore the units are farads per metre, i.e. the amount of capacitance per depth into the page.

We can interpret these capacitances by recalling the equivalent circuit of these self and mutual capacitances (Figure 24).

The meaning of the mutual capacitances for the 2 electrode system.

Zoom:A capacitance meter connected between the two electrodes would measure the parallel combination of capacitances, i.e.

Complete code sample

Conclusion

Capacitance is commonly used for sensing purposes because it enables relatively long range, contactless measurements. The most famous example of capacitive sensing is the touchscreen found in many portable electronics devices. Capacitance is also common for sensing the presence or absence of various materials, for humidity sensing, and more.

There are two main types of interface circuits for capacitive sensors. In many designs, an AC voltage source is used to treat the capacitance as a complex impedance, and the impedance measured using similar methods to that of resistive sensors. In other designs, changes in capacitance control the timing of an oscillator or the time constant of an RC circuit.

We have developed a method to calculate the capacitance of arbitrary geometries. You can use this to design capacitive sensors. For example, if the underlying mechanism involves changes in permittivity, then you run the calculations with different values of permittivity and examine the resulting changes in capacitance. If your design involves changes in geometry, then you can draw multiple geometries and calculate the capacitance for each one. In this way, you can trial different design concepts and identify the one that will lead to the highest performing sensor.

You will apply this knowledge in Assignment 2 to design your own capacitive sensor.

References

Ramon Pallas-Areny and John G. Webster, Sensors and Signal Conditioning, 2nd edition, Wiley, 2001.

Winncy Y. Du, Resistive, Capacitive, Inductive, and Magnetic Sensor Technologies, CRC Press, 2015.